In September 1916 George William Cotterill, was living in Magnet, near Waratah in North West Tasmania. Despite this, he considered himself to be from Beaconsfield, where he was born and where he may have left behind his wife (Eva May nee Trezise) and infant daughter Mavis Winifred, when he went to work in the remote mining town.

George was 24 years old, a labourer, 5 feet 5 ½ inches (166cm) tall and weighed 136 pounds (62kg). He had black hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion. He was missing part of finger from his left hand.

That month, as the war in Europe entered its third year there was an increasing need for more troops. One tactic was to appeal to patriotism – and even parochialism. In early 1916 Tasmania’s own battalion was formed and there was an informal competition between states to provide the most and the best troops.

There was also a referendum on conscription due in October 1916, and newspaper ads and articles increasingly gave the impression that men would soon be compulsorily drafted – if not worded in a way that gave the impression that conscription was already a reality. Tasmania now had a quota of 1100 men for September alone.

Just over 300 Tasmanian men enlisted during September 1916. On the last day of September George became one of them.

Application to enlist was more than just filling in paperwork. On the Saturday that George applied to enlist, he probably travelled to Waratah (the nearest larger town near Magnet) where he met up with a traveling army medical examiner. He was found fit to serve but would need to travel to Claremont (Hobart) to complete the enlistment process.

George was in Claremont camp just over a week later– one of 37 men who entered the camp that day. He formally enlisted in the AIF the same day, signing the first forms on the 11th of October with the final ones being stamped on the 13th. He was given the number 3022.

Almost straight away he was granted “final leave” and returned to Beaconsfield, where there was a farewell party in mid October, at which he received a knapsack Bible, pair of military brushes and a shaving brush.

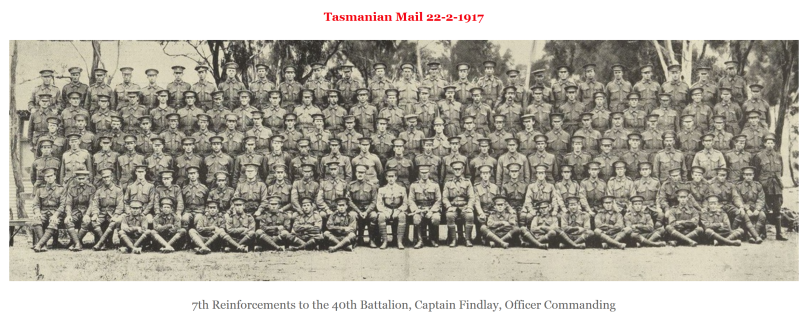

After a period of training at Claremont, George was appointed to the 7th Reinforcements of the 40th Battalion (10th Brigade, 3rd Division) on 2 February 1917. He departed overseas from Adelaide on 10 February 1917, sailing for England aboard the Seang Bee.

Generally, once Australians arrived in the UK they spent another 3 months training before proceeding to the front. For earlier portions of the 40th Battalion this had included recreation time in London – visiting tourist sites, marvelling at underground trains and deciding that it was all very different from Burnie.

George however had only been in the UK for just over two weeks when he was admitted to hospital with influenza. His family weren’t formally notified that he’d been ill.

After 11 days in hospital he proceeded to Dorrington (Bovington?) Camp. Bovington was a Command Depot, a place to convalesce and be prepared to rejoin his unit.

He finally departed Southampton for Le Havre on 30 August 1917 and joined the 40th Battalion in France. George can only have had about 8 weeks of UK training, but when he arrived in France his division were undertaking training there. Then, on 22 September, the Division was inspected by the Commander-in-Chief (Sir Douglas Haig).

Within 24 hours orders were received that the Division would move forward to Ypres to join the third Battle of Ypres. On 25 September the Battalion left Becourt, and after three days on the road reached Winnezeele.

Here the Battalion received preliminary orders for the attack.

The battle began at dawn on 4 October. The 40th Battalion was there until midnight on the 5th.

Another attack began on the 9th, but failed. It was attempted again on the 12th, and this attack continued until the 13th.

On 12 October 1917, during this battle, George was shot in the back. The wound was so severe that on 16 October he left France and was hospitalised in the UK at the 1st East General Hospital. His wounds were described as serious, and his wife was notified – but she didn’t receive the news until possibly as late as November.

Recovery took four months – he didn’t sail from Southamptan again until February 1918. Again, he spent time in a Command Depot, this time at Longbridge-Deverall near Sutton Veny (a venue that suggests that his recovering was thought to take less than 6 months).

George finally rejoined his unit in Rouelle France, on Valentines Day. The 40th Battalion were working on rear defences but returned to the frontline on the 16th, until they were relieved 9 days later.

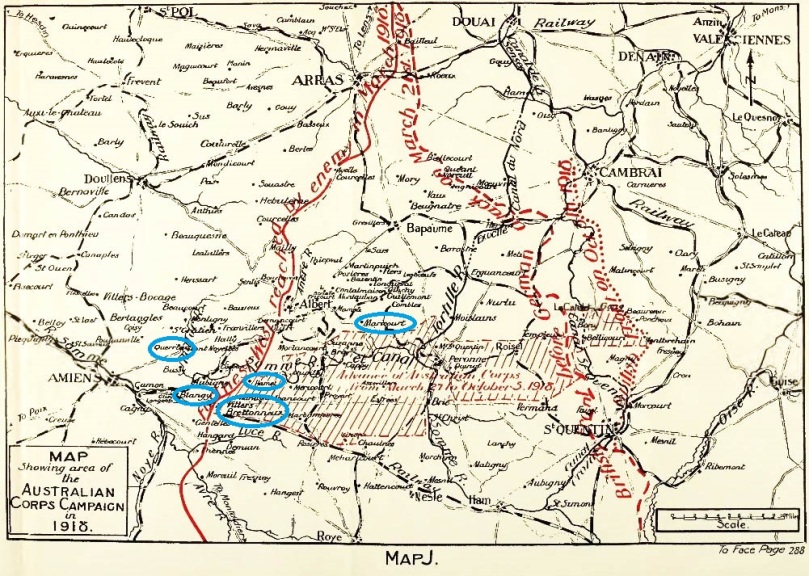

On 21 March the German Offensive began and George took part in some of the most well known Australian battles of the Western Front.

On 23 March the battalion headed towards Flanders, but were redirected towards the Somme. Over the next few days, as the situation at the front changed, the Tasmanians had their plans changed multiple times. They travelled by train, on foot and even by bus, coming under fire at times, and sleeping out in the open when required. On 28 March news was received that the Germans were advancing and that the Tasmanians were to advance at 4pm to seize the high ground near the village of Moriancourt, which had already been seized by the advance guard of the enemy.

As planned, the 40th Battalion advanced at 4pm. Due to transport difficulties in their move to the Somme, they didn’t have trench mortars, machine guns or heavy artillery. After an advance of 1200 yards, with the Germans firing on them, the Tasmanians “dug in.” 160 members of the battalion were killed, wounded or taken prisoner that day.

Over the next two days the Germans advanced in “waves” but were held back by the Australians. The 40th Battalion were finally relieved before dawn on 31 March. But were back on 3 April. Their position at Marrett Wood was heavily shelled over the next three days. Over the following month the 40th Battalion had three more stints in the front line, but even when “in reserve” found themselves heavily shelled.

In early May the battalion were ordered to occupy the village of Ville-sur-Ancre, but the information was incorrect and they were met with machine gun fire.

On 9 May the entire division was at Frechencourt where they were able to undertake sport and training until 22 May. The next stop was two weeks at Blangy-Tronville where they laid cable near L’Abbe Wood.

In June the 40th Battalion took part in the Battle at Villers-Bretonneux. At first, they were in support positions, but then moved to part of the front line east of the town, on the road to from Amiens to St Quentin, in crops of wheat. During their time in and around the town they took part in a number of attacks on the German trenches. This was the final significant battle of the Battle of the Somme.

On 22 June the battalion returned to Blangy-Tronville and the task of burying cable for a week. On 26 June they moved to Querrieu were there was again sport and training.

July was spent in the trenches east of Hamel.

On 4 August 1918 George was again hospitalised, this time with diarrhoea and dysentery. He was treated in France, but didn’t rejoin his unit in Rouelle until 8 October 1918. He then remained with his unit until he returned home.

While George was in hospital the Hindenburg Line (the German advance into France) was finally breached, and in October Australians began to leave the front line as the processes that lead to the Armistice began, so George never returned to the trenches.

The war ended in November 1918, but troops remained in Europe (many, including George, getting a period of leave).

George finally departed England on 27 May 1919 (6 months after the end of the war), and disembarked in Hobart on 12 July 1919, almost 3 years since he enlisted.

On 5 August 1919 there was a welcome home for him and two others in Beaconsfield’s Alicia Hall. George sat on the stage and was cheered by the crowd. The returned soldiers were awarded medals by the public, there was speeches and then the band played both inside and outside the hall. His name is now on the Beaconsfield Honour Roll now in the Beaconsfield Mine Museum.

40th Battalion, 7th Reinforcements: https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showUnit?unitCode=INF40REIN7

Timeline of the 40th Battalion http://www.40th-bn.org/timeline.html and https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U51480

George’s War Records https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Gallery151/dist/JGalleryViewer.aspx?B=3428348&S=4&N=21&R=0#/SearchNRetrieve/NAAMedia/ShowImage.aspx?B=3428348&T=P&S=1

Letters home from another member of the 7th Reinforcements/40th Battalion http://www.vandemonian.info/byers-family-related-world-war-1-roll-call

Arrival overseas and final preparation for battle https://anzac-22nd-battalion.com/training-camps-france/

The Australian Conscription Battle http://anzaccentenary.sa.gov.au/story/whose-side-are-you-on-australias-conscription-debate-in-1916/

Diaries of Tasmanians serving with the 40th Battalion www.tasmanianpioneers.com/blog/category/the-anzacs

Sir John Monash’s book about Australians in France in 1918 http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1302421h.html

[…] During WW1 Eva Cotterill nee Trezise’s husband, George, was at the front. […]

LikeLike

[…] Beaconsfield was where Grandpa’s aunts and uncles and cousins were. Three of his four grandparents were alive and living in Beaconsfield – as was one of his great grandmothers (Lydia Brown formerly Stonehouse nee Freeman). Beaconsfield however, was a different place than prior to the war. In 1914 the mine, the town’s main reason for being, had closed, and with it went most employment opportunities. Many people, like Grandpa’s father, were also changed – George had been seriously injured in the war. […]

LikeLike

[…] WWI George Cotterill returned home to his parents, his wife Eva and his daughter May, in Beaconsfield, where, in 1922 […]

LikeLike

[…] the mine closed. The boomdays were over. And then the war began. Two of her three living sons – George and Len – enlisted (Percy wasn’t old enough). While both returned home alive, Emma still […]

LikeLike