We might now live in a world in which we are able to hear about awful things almost immediately, and if we wish we can then observe every update in real time, however in rereading news reports of past tragedies, I can also see that we are today spared some of the grisly details that were standard fair in the past.

The pain and shock of a sudden loss is no different, however.

Oh, hard it is to part on earth,

With one we loved so dear;

But harder still it is to part

Without one farewell word or tear!

From Launceston Examiner 17 October 1913, In Memoriam notice for Thomas Floyd

The Tasmania Gold Mine 1912

Over the years there have been some high-profile tragedies in the Beaconsfield Mine – and others that have gone unrecorded except by the victims, such as my Great Great Grandfather Henry Cotterill, who lost his leg in accident that doesn’t seem to have ever even made the papers. However, Henry’s wife, Emma Maria Annear, had a sister who married a man named Thomas Floyd who was killed in the mine in 1912, and made national news. Thomas Floyd’s accident came just 6 days after the much more famous Mt Lyall Disaster in which 42 men were killed on the state’s west coast.

These days the Mt Lyell Disaster is still well known and commemorated annually, however the Beaconsfield accident seems to have slipped from public consciousness. In the Beaconsfield Mine accident just two men were killed, but at the time, the accident – especially the plight of Thomas’ widow, Sarah – was also high in the public mind, the two events linked as part of a bigger issue about mine safety and the risks taken by those workers and their families. (Illustrating links between mining towns, one of the men who was in the cage with Thomas was the brother of a man killed at Mt Lyell the week before.) The Mt Lyell accident prompted a Royal Commission into mine safety.

Thomas was 51 years old when he and another man (Murdoch Fraser Stewart) fell 900ft (274metres!) from the cage that was bringing them to the surface after a night shift, at 7.45am on Thursday 17 October. They fell between the cage and the wall of the Hart shaft, perhaps it was Stewart’s “bluey” coat that caught on the wooden lining of the shaft or tangled in the lines pulling the cage upward, or perhaps it was Floyd’s billy can. Either way, it was dark, and others in the cage could only feel and hear what had happened.

Floyd left ten children – one just a baby – and was presented in the media as a hard-working, “typical” miner, representative of “every man.” A biography on Ancestry says that he and Sarah were “staunch” members of the Auld Kirk at Sidmouth, even donating timber to restore it after it burnt down. Thomas was the superintendent of the church for many years. In memoriam notices show him as an adored and adoring father.

Stewart was just 22 years old and had been working at the mine for only a month, assisting to support his parents who ran the Winkleigh Post Office.

Thomas’ funeral was on the 19 October. He was buried at Beaconsfield. In compensation for his death, Sarah was paid a “pittance” from the mining company, which she considered “blood money” (Ancestry biography).

People all around the state contributed to the “Floyd Fund,” even while also canvassing for funds for the Mt Lyell victims. Towns held dances and other fundraisers to aid the Floyd family, sometimes simultaneously with raising funds for the Mt Lyell victims. Some of the money raised for her she used to buy a wedding ring in memory of Thomas. To continue to pay the rent on their cottage at Sidmouth, Sarah grew and sold vegetables and eggs, and took in boarders (Ancestry biography).

A family story compounds the tragedy, with his eldest son (another Thomas, aged 25 at the time) working above ground to bring the cage to the surface. This wasn’t mentioned in the inquest, but it’s not necessarily untrue either. Furthermore, just one year later, on 31 October 1913, the baby of the family, Arthur Richard, died aged 2.

Thomas’ death was not the sort of tragedy where there were photos for the newspapers to print, but there were plenty of witnesses and plenty of reporters happy to tell every sensationalist detail of what was heard and felt and seen as the men fell between the cage and the shaft wall.

Really, you don’t need to read the contents of articles with titles like this.

The Little Nell Disaster 1874

On Wednesday morning 19 February the steamer Little Nell left George Town for Launceston. As it travelled south it pulled into multiple ports where it picked up passengers. At Sidmouth, William McDonald boarded, and at Gravelly Beach, George Kerrison came aboard.

William was a 57 year old resident of Sidmouth, where until the 10th of the month, he had run a store, and lived in an attached cottage with his wife and children. On the morning of the 10th the entire family had been visiting relatives, the Lockwoods, when at 11am they heard there was a fire back at their home. Neighbours saved a small amount of their possessions, and also stopped the fire taking out a neighbour’s house. Despite being insured, the family lost over 100pounds due to the shop’s books being burned and therefore debts being unrecoverable. William likely boarded Little Nell to travel to Launceston to claim on his insurance for the fire.

George Kerrison was a 37 year old, locally born farmer. He and wife Selina nee Moore had 10 children (three had died in infancy). Gravelly Beach was the logical place for him to join the steamer, from his home in the Supply River area.

There were 11 people on board.

As Little Nell approached Launceston it and another ship, a tug, the Tamar, came close and an impromptu race was on! Those on shore saw Nell stop and then move off again even quicker. It was later speculated that the valve to allow excess steam to escape had been closed.

Just after midday, across from Freshwater Point the ship exploded. Those on shore saw pieces of ship and bodies fly into the air. A man working on the Rostella property at Dilston helped pull survivors ashore, and a father and son in another boat which had been observing the race, also helped.

McDonald was pulled onto a boat and taken to Launceston where they arrived at 8pm, and he was then taken by cab to the hospital. Although it was touch and go, he was one of only three survivors. In the ensuing search for survivors and wreckage, his insurance policy was found!

George Kerrison was less fortunate. It took days to find his body. His brother, Thomas, was vocal about the lack of any police assistance in the search, and also made the grisly discovery of the body of another victim.

The inquest was unusual in regards of what I’ve seen in other early inquests, in that it made a recommendation, namely that the government take a larger role in regulating steam engines.

George Kerrison’s relationship to me is convoluted. He was married to Selina Moore, who, after George’s death, married into the Stonehouse family when she married William (1836-1913), a brother of my 3x Great Grandfather Alfred Stonehouse. However, George was already linked to the Stonehouses, as one of his brothers had married a sister of Alfred’s in 1871, and there was to be at least one more marriage between the two sets of siblings during the 1880s.

As for William Mcdonald, one of William’s grandsons, another William Mcdonald, went on to marry Sarah Dinah Bilson Annear, whose father was brother to my gg grandmother, Emma Maria Annear.

The Little Nell explosion was not the first tragedy to strike the McDonald family. In 1859 the family was also in the papers, when their eleven year old daughter Margaret died from an overdose of Laudanum administered by her parents. And the fire and the explosion were not even the end of William’s disasters of 1874. In December the ship George Town Packet, was sunk off the state’s West Coast. William had been owner of the vessel in 1869, and while he had sold it by the time it was no longer trading on the Tamar, its loss may still have been keenly felt by him.

Inquest into the Little Nell explosion.

Death of Margaret McDonald here and here.

Campania Railway Accident 1916

Tasmania hasn’t had passenger train services within my lifetime, so stories of train accidents seem to be far from people’s minds and to have been lost. However, due to our mountainous terrain we have/had narrow gauge railways, which did and does lead to higher than average chances of trains coming off the rails. One of the worst – the worst? – was the 1916 Campania accident.

During WW1, travel was changing from being from horse drawn carriages to petrol engine cars and buses. Trains were the constant as these eras changed, and services were important and reliable ways to travel long distances. Just before 4pm, 15 February in 1916 a train from Launceston, carrying 200 passengers, was heading towards Hobart. It was nearing Campania around 4pm, when, just north of the town it came off the rails. (Possibly just near where Brown Mountain Rd heads off to the east, although if this is the case, I don’t know why the reports never say Lowdina?).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_accidents_in_Tasmania

https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/R/Railway%20accidents.htm

The driver and six passengers were killed and 31 injured. A number of the victims were young men either on their way to enlist, or returning to camp after final leave. To my eyes, it also seems that a fair number of the injured were from Sidmouth.

Amongst the injured was my Great Great Aunt Elizabeth Hinds nee Annear, who was sister to my Great Great Grandmother Emma Maria Annear (and another sister of Sarah who was married to Thomas Floyd, above).

Elizabeth suffered a dislocated left shoulder, and was on the train with four members of her family, including two of her sons. The three young men in her party were all on their way to enlist.

Henry George Hinds age 20, a labourer, who had his left foot amputated in the accident.

William Annear Hinds age 33 (born 1882), suffered cuts on his face. Did end up enlisting in September 1916, and serving.

Amy Hinds nee Westwood, wife of William. Gash on left ankle.

And her nephew (son of her brother William and his wife Emma Louisa Nicholls), David Annear age 22, an orchardist, who suffered cuts and shock. David was able to enlist on 3 March 1916. (He served in a Cycle Regiment, which is going to require some more research!)

Due to the larger number of other victims from Sidmouth, it’s likely that as well as dealing with injures of family, these people were also grieving injuries and losses of friends.

By 1916 cameras were portable, and photos were taken at the scene so soon after the accident that people are still being removed from the wreckage in some. These photos appeared in newspapers, with no modern concern for the victims’ families or the ethics of buying a newspaper in order to see that sort of tragedy.

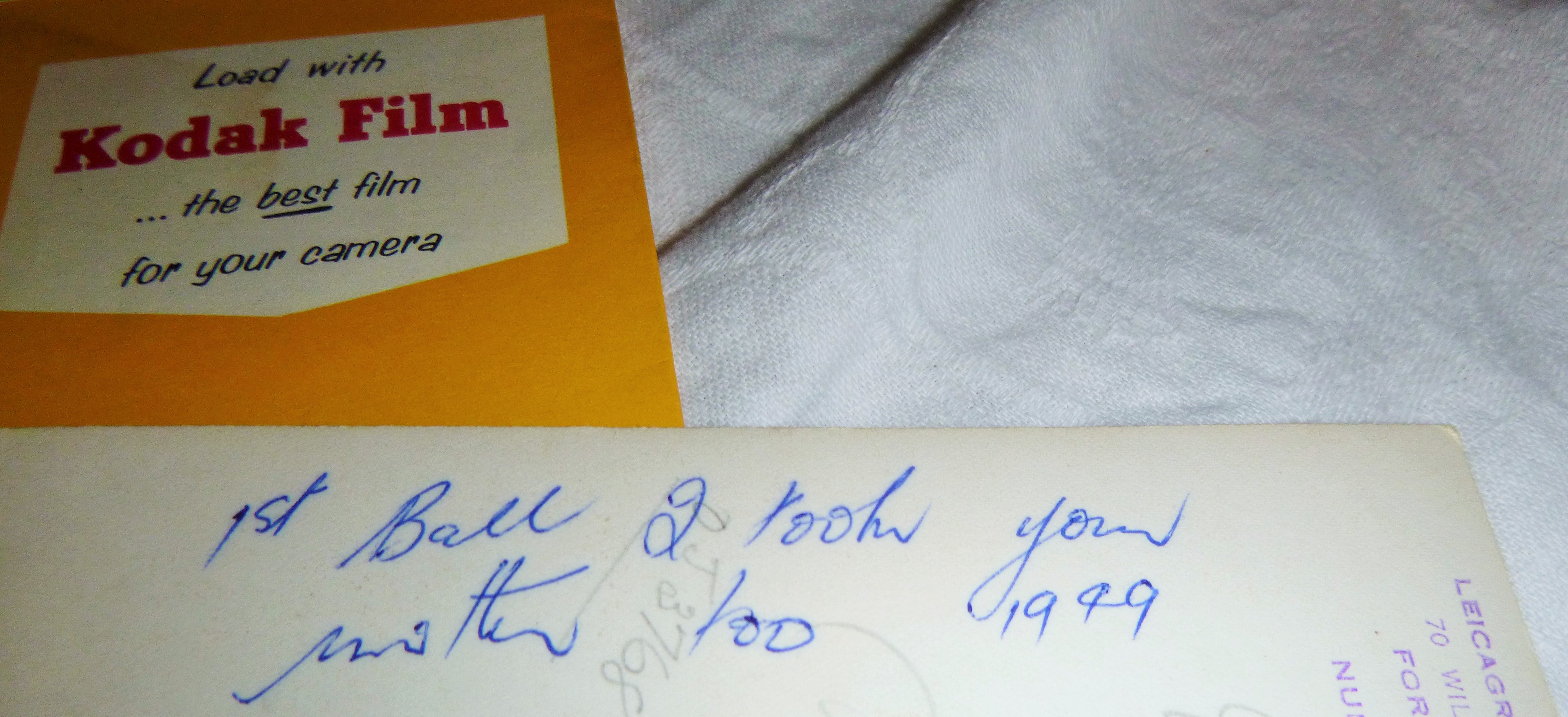

Photos from here: http://tps.org.au/bb/viewtopic.php?f=6&t=662 These were postcards, taken so soon after/during the accident that victims are still being removed from the carriages. More photos: https://www.facebook.com/MercuryNewsInEducation/posts/tasmanias-worst-train-crash-occurred-near-campania-100-years-ago-this-week-five-/1709553205998073/ And one postcard is from Leski auctions website: https://www.leski.com.au/m/lot-details/index/catalog/434/lot/130898/Tasmania-Campania-lsquo-Railway-Accident-near-Campania-Showing-The-Curve-rsquo-real-photo-card-H-H-Baily-Photographer-Hobart-showing-the-aftermath-with-upturned-Locomotive-and-Passenger-Cars-being-inspected-used-under-cover-with-message-on-back-couple-of-light-creases?uact=5&aid=434&lid=127882¤t_page=0